| Neil Gaiman has his own Web site which includes an on-line journal. | ||

| Click on a book's image or title to order from Amazon.com |

Neverwhere

Avon, PB, © 1996, 288 pp, ISBN #0-380-78901-9Reviewed November 1999

Based on his BBC TV series of the same name, Neverwhere falls into the category of "modern urban fantasy". The old cities around the world have hidden 'undergrounds' where people who fall out of society end up living, largely forgotten and unseen by the people above-ground. Stuck in an unhappy life as a paper-pusher, Richard Mayhew one evening rescues a young girl whom he finds bleeding on the streets of London. This pulls him into the dark, magical world of 'London Below', as he finds that his friends have forgotten him and can only see him - briefly - if he acts forcefully to attract their attention.

The girl turns out to be Door, the youngest daughter of a family who can open doors - physical and metaphysical - to almost anywhere. Her family has been killed, and she's running from her pursuers - the bestial and nigh-undefeatable Mr. Croup and Mr. Vandemar. With the terrible duo threatening his life, Richard hooks up with Door to help her in her quest to learn who killed her family.

The setting is based around the London Underground, the subway system also known as the Tube, and the book sports a neat map of the system in the front, mainly neat because it lists opening and closing dates for most of the stations. London Below is sort-of divided up into kingdoms and other places of power, with names taken from the Tube stations: There's Earl's Court, there's a gentleman named Hammersmith, the Black Friars, the angel Islington, a literal Knightsbridge, and so forth. (No Paddington Bear, sadly.) Door, Richard, and their entourage - Door's mysterious protector the marquis de Carabas, and her hired bodyguard Hunter - make their way through London on Door's quest, followed by Croup and Vandemar.

The book is, essentially, a quest, partly Door's, but mainly Richard's. It's also an epiphany, as Richard grows out of the shell that had hardened around him in his life in London Above. This is a somewhat fuzzy development, though, apparently spurred on more by pure shock at being thrown into such a different world than by clear-cut growth experiences. There's certainly some similarity there, but I think Gaiman dances around it more than fully explores it. The strongest feeling we're left with is that Richard is forced to contrast his friends-in-adventure in London Below with his well-meaning but not entirely satisfying co-workers and acquaintances in London Above.

I find Gaiman's prose style somewhat frustrating, especially since it's almost nothing like his comic book style in Sandman and elsewhere. He writes with the whimsical approach to dire events that is so evident in Douglas Adams' novels - not too surprising, I guess, since one of Gaiman's early works was a Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy guide called Don't Panic, but as when I read Gaiman's collaboration with Terry Pratchett, Good Omens, I often felt like I was reading an Adams rip.

Overall, Neverwhere is a good read, and makes me curious to see the TV series, but it seemed a bit too much flash and not quite deep enough to be really satisfying.

American Gods

Harper Torch, PB, © 2001, 588 pp, ISBN #0-380-78903-5Reviewed June 2002

American Gods seems slightly misleading: Suggesting gods springing up in keeping with the culture of modern America, the book focuses more on the old gods from other lands who immigrated here (at least in one aspect) when humans did. While there are gods of modern culture, they're the titular antagonists and mostly stay off-stage.

The book is told from the perspective of Shadow, a man who's just been paroled after 3 years in prison. He finds that his wife and best friend have been killed in a car accident, and his job prospects have dried up. Then a mysterious man named Mr. Wednesday hires him as a bodyguard. Wednesday is one of those immigrant gods, and he's recruiting other old gods - who through lack of worshippers have mostly become societal cast-offs, if they survive at all - to help in the coming battle with the new gods, the gods of television and internet and secret government agencies.

Shadow, numb inside, takes all of this in as good a stride as anyone could be expected to, though he is somewhat disturbed that his wife seems to be lingering in the world after her death. Moreover, the new gods seem strangely interest in Shadow's existence, and not just because of what he can tell them about Wednesday's plans.

American Gods is a travelogue both of old gods who have come to America, and of the places of power that have sprung up around the country: Roadside attractions like Wisconsin's House on the Rock, the geographic center of the United States, and so forth. There are lengthy passages in which Shadow bides his time in a small Minnesotan town between missions with Wednesday. And of course there's the climactic battle, which is not what we've been led to expect (and that's a good thing).

As a writer, Gaiman has two essential flaws: His plots are generally simple or perplexing, and he has trouble structuring his stories. His yarns succeed or fail based on how well he executes his basic ideas, and how involved one gets with his characters. Fortunately, American Gods has just enough of a plot - and a plot twist - to be satisfying, and his characters and dialogue are both engaging (happily he seems to have left behind his faux-Douglas Adams voice from Neverwhere and Good Omens).

While Shadow's character is flat much of the time, his basic demeanor combined with the death of his wife (and his prospects for his post-jail life) make this believable. He's willing to accept anything, and not get too involved with it. Wednesday is his foil, a strong personality but one with a somewhat skewed look on life. Gaiman employs Shadow's penchant for coin tricks and Wednesday's for con games to good metaphorical effect, although they also provide a window onto the plot.

The tour of America is not always successful. Shadow's stay in Lakeside, Minnesota drags at times, and the whirlwind descriptions of various minor attractions around America give us the feel of an overview of the land without really conveying an understanding of why those attractions are so important in the story. The detail lavished on them feels gratuitous, and occasionally it feels like Gaiman has lapsed into some sort of "bestseller writing style", taking his readers through all the trivial details of the scenario when it would have been more satisfying to cut to the chase.

Despite this, the book reads surprisingly quickly, and mostly moves right along. The last 150 pages or so are very lively and exciting, culminating in the climactic face-off(s). Gaiman successfully takes Shadow through his story arc, although at the end it's not entirely clear that he's really gotten himself together as a result of (or even despite) his ordeal. And Gaiman still has his sense of humor, which has gotten wryer as it's become more subdued, which overall is a plus.

So I'd certainly recommend American Gods to fans of Gaiman, or fans of fantasy. Fans of tightly-plotted stories or of science fiction might find it harder to get into, although Gaiman's basic earnestness is endearing. It may not be an ideally rewarding novel, but it's certainly fun.

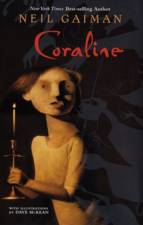

Coraline

Harper Collins, HC, © 2002, 162 pp, ISBN #0-380-97778-8Reviewed December 2003

Coraline is a story for young adults. It's a dark tale, somewhat reminiscent of Gaiman's comic book series The Sandman. A young girl named Coraline Jones is unhappy with her life. It's dull. She goes out exploring the land around the house where a family rents a flat and has some modest adventures, but mostly she just wishes for something more interesting than her parents who mostly ignore her, the two old ladies in the adjacent flat, and the crazy old man in the upstairs flat.

However, Coraline's flat has a door which doesn't open - except that with a particular black key, it does. Despite warnings, Coraline goes through the door and finds herself in a twisted - but interesting - duplicate of her house, with her "other mother" and "other father", and peculiar versions of everyone else she knows. And also, a black cat which can talk in the other place, but whom she sees in both places. Her other mother wants her to stay with them so they can live together as a family and so the other mother can love Coraline.

When Coraline declines, the other mother steals her real parents, and Coraline is forced to play a game with the other mother to find her real parents in the slowly-changing other world and bring them back to their home.

Coraline is a book with the trappings of a great fantasy story, but not much of the substance of a great fantasy story. Coraline is only a one-dimensional character, so she has little internal conflict to add depth to her external struggles. Her quest to rescue her parents is simply a mechanism to provide a few inventive challenges or backdrops, but it's not particularly interesting or inventive in and of itself.

In short, the story shows all of Gaiman's flaws as a plotter that he rectified so effectively in his novel American Gods. Gaiman is, at heart, a colorist: He creates settings and moods, and that's fun as far as it goes, but for someone who's read a lot of his work - like me - I've seen a lot of this sort of stuff before and I'd like more meat to the story and characters. When Gaiman does so, he produces some great work; when he just does the setting and mood, it feels lightweight.

The book is illustrated by Dave McKean. I have long disliked McKean's artwork, finding it stylized to no useful end, and his storytelling abilities in comic books to be extremely limited. Here, it's even worse. The cover illustration - presumably of Coraline herself - is one of the most grotesque covers I can recall offhand, and - again - to no good effect. The interior illos - in pen-and-ink - are no better, not usefully illustrating the story or providing any twists on the narrative's descriptions, and often showing an unfortunate lack of perspective. I've avoided other Gaiman work because of McKean's illustrations (such as The Day I Swapped My Dad For Two Goldfish), and the illustrations in Coraline make me think that this was not a bad decision.

I also wonder what the moral of the story is, since it's told in that storybook style which suggests that it ought to have one. That adventure is as close as your own home? That you should go exploring through strange doors and your parents won't stop you? That the way to win your parents' attention is to put them in danger and then save them? That there's no place like home - not even your other home?

Coraline is a quick read, and it trips the imagination, but it feels like it could have been a lot more, and it's just not.

hits since 13 August 2000.